Rhinitis is defined as a non-infective nasal disorder of more than eight-weeks duration which is characterised by inflammation of the nasal mucosa (Scadding et al, 1995).

During the past two decades, many developed countries have seen an increase in the prevalence of asthma, eczema and allergic rhinitis. In some places the incidence has doubled over the past 10 years (ISAAC, 1998).

Allergic rhinitis is one of the most common chronic conditions and affects 16-23% of the UK population (ISAAC, 1998). There is evidence to show that it commonly coexists with asthma.

Rhinitis often receives less attention than it deserves from health care professionals. People with the condition often attend asthma clinics, where the tendency is to focus on what is happening from the neck down, to the detriment of the upper part of the respiratory tract.

Function of the nose

- Acts as an air-conditioner:

- Heater – the nose heats air inhaled through it so that the air is at an appropriate temperature when it reaches the nasophyarynx;

- Humidifier – the nose humidifies inhaled air, as dry air can irritate the lower airways;

- Filter – the nose plays a key role in filtering particulate matter and some chemicals out of the air we breathe, in particular nitrous oxide and sulphur dioxide;

- Local defence: mucus is produced to help remove local irritants;

- Vocal resonance: through connection with the sinuses, the nose helps to produce resonance for the voice, which is why voice tone changes when we have a blocked nose;

- Olfaction: the nose is the organ of smell.

However, the symptoms of rhinitis, such as a blocked nose, can result in the lungs receiving cold, unfiltered air. The presence of rhinitis may, therefore, exacerbate coexisting asthma.

Rhinitis has a significant impact on quality of life. A blocked or running nose can affect everyday activities, causing irritability and debility. This, in turn, can affect people's ability to function effectively at school or work and can have a negative effect on their social life.

With children, in particular, nasal congestion can cause mouth breathing, resulting in a dry, often sore, mouth and throat and a 'nasal' voice. It can also cause snoring and sleep disturbance.

The condition can be categorised into allergic, non-allergic and vasomotor rhinitis.

Allergic rhinitis

This is the most common allergic disorder and more than three-quarters of children with rhinitis have a presentation that is associated with allergy.

The immune response is primed by previous contact with an allergen. Once this has happened, subsequent contact with the allergen causes mast cells in the nasal mucous membrane to be coated with an antibody belonging to the immunoglobulin E class (IgE).

When the antigen (pollen, for example) interacts with the IgE antibody on the mast cell surface, mast cell degranulation occurs. In what is known as the early phase, a range of mediators are released, including histamine, platelet activating factor, slow-release substance of anaphylaxis, 5-hydroxtryptamine and chemotactic factors. The release of these agents results in eosinophils being attracted to the site.

The late phase is identified by eosinophil migration and the recruitment of many other cells, including basophils, neutrophils, T-lymphocytes and T-helper type 2 cells, which are responsible for the further release of chemokines, basic proteins and chemotactic factors. This is a self-augmenting process that is part of the inflammatory cascade.

Allergic rhinitis may be seasonal or perennial. Seasonal rhinitis is caused by allergens produced at a particular time of the year, such as trees, grasses or pollen.

Perennial rhinitis is caused by factors that may be present all year round, such as house-dust mites.

Acute allergic rhinitis is most likely to be seasonal and quickly produces symptoms, including nasal itching, sneezing, a watery nasal discharge and a blocked nose. It is not unusual for eye and skin irritation to accompany the process.

Perennial allergic rhinitis does not usually present such dramatic symptoms. Symptoms such as a blocked nose and a mucoid nasal discharge may be present both day and night but patients sneeze less than with seasonal rhinitis.

Non-allergic rhinitis

This is caused by extrinsic factors, such as drugs or industrial particulate matter, which may be related to the affected person's occupation or intrinsic factors, such as hormonal mediators during pregnancy.

Vasomotor rhinitis

There is often no identifiable cause of vasomotor rhinitis, but it is associated with a disturbance to the autonomic control of the nasal mucosa. It results in nasal congestion, excessive mucoid discharge and post-nasal drip.

History and examination

As with all diseases, a careful history can clarify the diagnosis and may also provide an insight into what is provoking the symptoms.

Nurses should ask about possible precipitating factors. Some may be obvious but others may need a degree of detective work to establish the connection. A family history of asthma, eczema or other atopy will make a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis more likely. Such a history may also seperate allergic rhinitis from that caused by systemic disease.

Other conditions, for example immunological diseases or granulomatous diseases, such as Wegener's, may present with nasal blockage and discharge. Early differentiation of these from allergic rhinitis is important.

History-taking should be followed by examination, which may also help to exclude systemic disease. If there is doubt about the cause of the symptoms, or if they are atypical of allergic rhinitis (unilateral nasal discharge, for example), specialist referral is advised.

Skin-prick testing

Skin-prick testing can be a useful adjunct to diagnosis, especially when common allergens, such as house-dust mites or pollen, are implicated.

Management

Avoidance

The first line of management should be avoidance, where possible, of the provoking factors. For example, if a person is sensitive to grass pollen he or she should be advised to stay away fom grassy areas during the grass pollen season, especially when the grass is being cut. Patients can also be advised to keep windows shut during the pollen season.

Avoiding other allergens, such as house-dust mites, can be more difficult. Nurses should advise patients on how to reduce house-dust mite levels through appropriate washing, cleaning and ventilation. The use of mite-proof bedding may also reduce exposure.

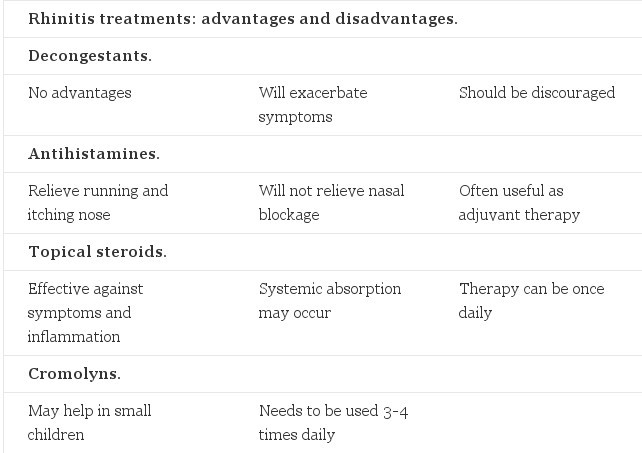

Decongestants

These are often the first line in self-management because they are obtainable without prescription and may provide initial relief. However, the continued use of decongestants can itself lead to congestion and rhinitis so patients should be discouraged from using them for more than a week.

Antihistamines

These have a role to play in the management of rhinitis. They act against histamine, but their success may be limited by the presence of mediators other than histamine in the inflammatory cascade.

Antihistamines provide symptomatic relief but do not reduce the associated inflammation and, therefore, do not affect nasal blockage. The side-effects include drowsiness, which may affect the patient's ability to drive or operate machinery. Some antihistamines now have a reduced tendency to cause drowsiness.

Topical steroids

Topical steroids are the mainstay of treatment in the therapeutic management of rhinitis. They reduce nasal congestion and relieve the ocular symptoms that are associated with allergic rhinitis.

Topical steroids are now available for adults and children over the age of four, and those with low bioavailability are the preferred choice. This is particularly important if the patient is already taking inhaled steroids for asthma.

Cromolyns

Sodium cromoglycate may be used in young children, but is less effective than topical steroids and must be used three or four times a day.

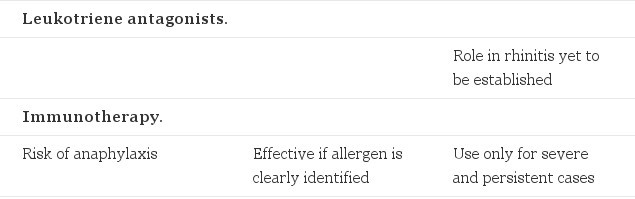

Leukotriene antagonists

These drugs act on the arachidonic acid pathway, an important part of the inflammatory cascade. Their role in rhinitis has not been established but they have been shown to be as effective as antihistamines. The results of comparitive trials against topical steroids are not yet available.

Immunotherapy (desensitisation)

This should be reserved for patients who have severe and persistent symptoms after a clear diagnosis and the identification of allergens. Because of the risk of anaphylaxis during desensitisation, the procedure should only be carried out in centres where there are resuscitation facilities.

Summary

The succesful treatment of rhinitis can be very satisfying, both for the patient and health professionals. The symptoms can be persistent and debilitating, and may have a serious impact on lifestyle. In most cases, a combination of avoidance or reduction of exposure to the provoking factors and treatment with a topical steroid will result in a dramatic improvement in symptoms within a day or two.

© Linda Pearce RGN, SCM, OHNcert, NARTC Dip Asthma Care, NARTC Dip Psychology of Compliance, NPract Dip. (1998) Nursing Standard 94, 39, 56-57.

References

- International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee (1998) Worldwide variation in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema. The Lancet. 351, 9111, 1225-1232.

- Scadding GK, Drake-Lee A, Howard P, et al (1995) Rhinitis Management Guidelines. London, British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Further Reading

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Andersson B, Ferrie PJ (1993) Comparison of powder and aerolized budesonide in perennial rhinitis: validation of rhinitis quality of life questionnaire. Annals of Allergy. 70, 3, 225-230.

- Pedersen PA, Weeke ER (1983) Asthma and allergic rhinitis in the same patients. Allergy. 38, 1, 25-29.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus